[The ongoing series of guest articles continues with this essay by Amanda Jernigan. Amanda is a writer living in Guelph, Ontario. She currently works for Porcupine's Quill, a fine imprint of the small, Canadian variety.]

Intertidal:

Travels in a Moral No-Man's-Land

by Amanda Jernigan

Photograph by Erin Brubacher

It has now been almost a year and a half since we woke up on a morning in mid-September to a phone call telling us to turn on the TV. Since then the world has gone galloping warwards, committing all sorts of injustices in deed and speech, and all this time I have been silent.

I've spoken, sure - I've griped about the news to friends and family, in desultory conversations had while chopping onions or driving to work. But as for serious expression - language polished by thought polished by language? Nothing.

Andrei Alezseyevich Amalrik says, 'If a person refuses the opportunity to judge the world around him and to express that judgment, he begins to destroy himself before the police destroy him ... ' I encountered this quotation not long after that September day, and the words have lingered in my mind as a reproof to me.

Why silent?

At first, I think, I was in denial. In October of 2001, my partner, John, and I headed out to the Canadian Maritimes. We spun down the 401 west to Montreal, took Highway 20 up into the flat lands of Quebec, and as the odometer worried over our distances, the dashboard clock ran through its repertoire of figures, and every hour on the hour 'bing, bing, bing' would come over the radio, signalling the news. We would fall helplessly silent, then, as we waited to hear what new bad thing had happened. It seemed as if the anthrax scare was following us from city to city; in fact there was a general anthrax scare, but I didn't put this together at the time, as we moved between CBC frequencies, each one bringing its dire local tidings. After a good 600 K of this I turned off the radio and put on a tape.

It was partly fear I stewed in, riding out those eastward hours, but it was also anger - anger at the abstract, uncontrollable horrors in the world at large which were imposing themselves on my basically happy life. And then from anger I would move to shame, realizing there have always been horrors, that they aren't abstract, and that I had always gotten along by more or less blithely ignoring them.

Some weeks later, in the library at Mount Allison University, I was doing research towards a paper on the poetry of Peter Sanger - reading texts on 19th century farm implements and 17th century alchemy. I was feeling rather smugly away from it all, when I came across a poem of that title: 'Away from it All', by Seamus Heaney.

A cold steel fork

pried the tank water

and forked up a lobster:

articulated twigs, a rainy stone

the colour of sunk munitions....

I should have taken my cue from that analogy, but the full significance of Heaney's seemingly idyllic lobster boil didn't hit me until line twenty, when 'quotations start to rise / like rehearsed alibis'. The narrator recalls a line from the memoir of Czeslaw Milosz: 'I was stretched between contemplation of a motionless point and the command to participate actively in history.'

I sat there in the library like the lobster at the end of Heaney's poem: fortified and bewildered. In one fell sentence, Milosz had mapped the queasy intertidal zone between my public values and my private life.

Allow me to explain. I was twenty-two years old at this time. I had only just emerged from the thicket of adolescence, and was enjoying the open road of adult life. I had a passion - literature - and a love, the aforementioned John. I had just begun to focus the flailing energies of my teenage years into something resembling real thought. The world was courting me with its age-old mysteries - love and family, friendship and its dissolution, death - and I wanted to live in the same world that the writers I respected had lived in, to build on the scaffolding they had established. The political disasters exploding in the world around me implied too great a discontinuity for me to face them willingly. I felt like V. S. Pritchett, speaking about the Second World War: 'Looking at the war egotistically, from a writer's point of view, it was a feverish disposal and waste of one's life.' Or - perhaps more aptly - like Walt Whitman, in the early days of the American civil war:

Year that trembled and reel'd beneath me!

Your summer wind was warm enough, yet the air I breathed froze me,

A thick gloom fell through the sunshine and darken'd me,

Must I change my triumphant songs? said I to myself,

Must I indeed learn to chant the cold dirges of the baffled?

And sullen hymns of defeat?

But anyone who poses such questions in the first place must. My lobster shell of fortified bewilderment could only hold out against the sea-change for so long.

But even once my shell was cracked, my bewilderment persisted. I wanted, now, to engage in debate, but I didn't feel like any real debate was happening. The actual issues at stake - if issues there were - seemed to abide on some separate level, far below our feet, while we went baffling on above them, talking about 'homeland security' and 'chasing the terrorists out of their caves' - expressions which oh-so-easily, by a series of greased non sequiturs, morphed into 'global security' and 'chasing Saddam out of his palace'.

I managed to overcome at least a bit of my bewilderment when I stopped, for the most part, reading same-day news, and started reading next-day (next-week, next-month) commentary. There was something in the polished prose of a piece in Harper's, the measured gravity of a speech on the CBC, that made me feel that at least there were issues, realities, and that one might weigh them, count, divide.

But a problem remained. Even primed for speech, I stuttered, unable to figure out whom I might address. As I said before, I was talking casually, already, with family and friends. I was passing on the Internet petitions as they came around, and came around again. And I was listening to those assured voices on the radio. But there seemed to be no movement that I could tap into, no union of like minds. It seemed as if, though I could think and feel, I might as well have been a lobster still, insofar as communication was concerned - a lobster about to be cooked.

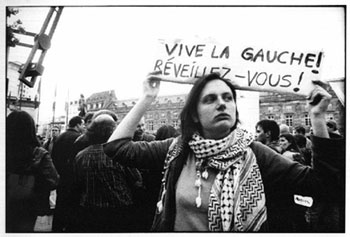

A good friend of mine, a photographer and artist-at-large named Erin Brubacher, took a picture last year while she was living in France, at a student protest that took place around the time of Le Pen's electoral successes. The photograph shows a young woman, clutching in her mittened hands a sign that says, 'Vive la gauche!' And then, beneath it, an impassioned afterthought, 'Réveillez-vous!'

Réveillez-vous. Exactly. I knew that there were people out there who thought like me. Where were they? Why this protracted - and perilous - silence?

(A silence, come to think of it, reminiscent of my own.)

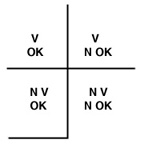

I read a story by Darryl Whetter called 'Kwump Kwump Kwump', in the fall 2002 issue of The New Quarterly. The story deals with a man's experience of the FTAA protests in Québec City. Prior to the protests, the protagonist, Chuck, attends a strategy meeting with other activists:

'... Let's start with The Grid.'

Hairy people without shoes began laying masking tape onto the blue carpet to form abrupt, angular letters.

'The people you like to go for beers with are not the same people you should go into Confrontation with in Quebec. You must be part of a unit to be strong, and these units will break apart if the members don't share the same attitudes about Direct Action. Let's all step over to The Grid and run through a couple of Scenarios.'This isn't so bad, Twister for revolutionaries.

'In my top - which is it again? - left, we have 'Violent But I'm OK With It.' To its right is 'Violent But I'm Not OK With It.' Bottom left it's 'Non-Violent And I'm OK With it,' then 'Non-Violent, Not OK.' ... Let's say we're walking down one of the march streets and someone shatters a McDonald's window. Find your place on The Grid. Do you think breaking the window is violent or not, and is that OK with you?'

Chuck shuffled with the big group into Violent and OK. The remaining third filled out the Violent and Not OK square, leaving Kir free to strut between both bottom quadrants.

To me, this scene - this babble of Ns and Os and Vs and Ks, this shuffling - seemed to signify exactly what was wrong with the political left. Well, I'm not really OK with that, but if you're OK with that, well, that's OK by me. Have we become so 'tolerant' of the opinions of others that we've forgotten to have opinions of our own?

In the January issue of Harper's Magazine, Thomas de Zengotita speaks to this, in an article called 'Common Ground: Finding Our Way Back to the Enlightenment'. He argues, among other things, that the postmodern cultural relativizing in which Liberal-thinking intellectuals have engaged for the last thirty years has happened at the expense of political unity:

Hopeful imagery involving mosaics and rainbows can no longer mask the truth. Except for undeniable gains made by certain members of certain groups in privileged Western countries, things are getting steadily worse for the wretched of the earth and for the earth itself. In the face of this trend, the response has been - incredibly - to repudiate the very notion of ideological unity, though the cause of progress will surely suffer if only fanatics and imperialists can achieve it.

So what to do? De Zengotita's admonishment to 'work out such an ideology, one that embraces diversity and transcends it' left me less than clear on this. Still, de Zengotita gave me some hints.

At the beginning of his article, de Zengotita writes about a friend who, after '9/11', 'spoke out loud and clear, holding the United States' support for corrupt and terrorizing regimes historically responsible for the conditions that produced the terrorists and shaped the views of the millions who applauded their action.' It so happened that this same friend had 'lost a brother to terrorism on Flight 103 over Lockerbie in 1988'. Someone told de Zengotita: 'That's what I don't get.... How could Mr. D. think the way he does after what happened to him? It doesn't seem natural.' De Zengotita's reply went something like this: 'Mr. D.'s core belief is that every human life is as valuable as every other human life, that every mother's loss, every brother's loss, is as terrible as any other....' For de Zengotita, this is a prelude to talking about Enlightenment principles dependent on 'that fundamental identification of each of us with all of us, with the sheer human being abstracted in the ideal from concrete contexts of history and

tradition.' These are principles to which, he claims, we still cleave, and ones we must re-embrace if we are ever to achieve unity in progressive politics.

De Zengotita's argument is well-wrought and persuasive. I will not try to reproduce it here. But I do want to seize on something from that anecdote: 'every human life is as valuable as every other human life.'

Now, I would sign my name to that. Intellectually, I cleave to that equation, and I would passionately defend it in any debate. And yet...

My father is a mathematician, and while I haven't inherited the fascination with numbers, the patterns of thought have come down to me; I like to simplify these moral equations until I come up with an irreducible law. In this case: if I really believe that every human life is equal to every other, then the prospective loss of the life of some young Iraqi man is equal to the prospective loss of my own John Haney. Then must I not go to the same lengths to protect the life of that young Iraqi as I would to protect the life of John? And how far would I go to protect John? I would like to think that I would give my own life - I must think that. Then must I not also be prepared to give my life for that young Iraqi?

I can do the math. Yet you do not see me signing up with 'Truth-Justice-Peace Action Iraq' to be a human shield.

Is this hypocrisy? Cowardice?

Another equation comes into play, here. The destruction of life is bad only insofar as we believe life to be good. That is to say, we grieve only insofar as we cherish. In order to actually hop on a plane to a war zone, leaving John, leaving my family, leaving my work, perhaps leaving my life, would I not in some way have to kill in myself the very values that I'd be seeking to affirm?

Let the good in the world equal positive n. Let the bad in the world equal negative n. Your mathematician-cum-activist is left with the great white zero of inaction. We are back in the intertidal zone.

Perhaps it is just that no matter how passionately we believe something intellectually, if we can't feel it, it's no good to us. And even when I try, I cannot make myself feel for the loss of a stranger as I feel for the loss of a friend.

And yet, I can.

My parents read to me every night when I was a child, and even into my early teenage years, as I was lucky in having a brother and sister who were still young enough then to demand the nightly ritual. Sometimes, those later years, I would read aloud a bit myself. One of the books we worked through as a family was The Yearling, by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. As my mother got into that last sentence, that Somewhere beyond the sink-hole, past the magnolia, under the live oaks ... , her voice began to quake. She passed the book to my father, who lasted about three words longer. The task of finishing the book at length devolved to me, though I barely managed to get out the gone forever through my tears.

A similar family cry-in followed the death of Thorin Oakenshield in our reading of The Hobbit.

If writing could make me grieve sincerely for a deer, even for a dwarf-king I never knew, then surely it could make me grieve for a human being.

And it did. For I was brought to tears for Gulley Jimson in The Horse's Mouth, for the aging Morag Gunn in The Diviners, and, moving into nonfiction, for Joseph Brodsky's parents, who died an ocean away from their exiled son, and for the destitute Gudgers'children in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, whom Agee imagines dreaming, it will be different from what we see, for we will be happy and love each other, and keep the house clean, and a good garden, and buy a cultivator, and use a high grade of fertilizer, and we will know how to do things right; it will be very different....

This idea that literature can help us empathize with others - even with people very different from ourselves - is not a radical concept. At least, it didn't used to be. George Eliot's artistic credo rested on the idea of the 'sympathetic imagination'; Shelley wrote that 'A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensively and comprehensively; he must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains and pleasures of his species must become his own.' When I ventured this notion in an undergraduate essay, however, it was met with shocked resistance. I had quoted Steven Heighton, a neo-Romantic if ever there was one, in his essay 'Horse & Train':

Art, and literature above all, is uniquely equipped to convey that indispensable facility, that rare and socially redemptive force, the habit of empathy - of trying to see through the eyes of others and to feel with another's body and heart.

The note my professor scrawled in the margin read, 'He's condoning appropriation of voice!!!' Did I mention that this essay was for my course in post-colonial-literature? Yes, well. Perhaps I should have known better. Still, I was wounded by those exclamation marks, and indignant about the assumptions they implied.

Needless to say, I read with delight some years later Stephen Henighan's essay 'The Terrible Truth About "Appropriation of Voice"'. Henighan quotes a line from a publisher's web site that urges: 'One rule of thumb a writer might consider in choosing a story from a culture other than their [sic.] own - is the culture a fragile one?' He responds:

The assumption behind this statement is that one can repair inequalities of access to publishing opportunities and media attention by restricting the subject-matter of writers seen to be occupying positions of relative privilege. Yet such a policy would do nothing to right wrongs or correct systemic imbalances; its only real effect would be to encourage a tepid, half-articulated literature.

True. And Heighton may not even have been talking about writing. That quotation from 'Horse & Train' could just as easily have had to do with reading. But the spectre of appropriation of voice has cast such a long shadow that we've begun to feel that not only mustn't we write about characters unlike ourselves, we mustn't read about them either - at least, not with any hope of understanding. And this is dangerous. Henighan writes:

It has become a commonplace among Toronto-based cultural outlets (and increasingly among those based elsewhere), to speak of 'the "appropriation of voice" debate'. This media sham has hoodwinked us. No such debate has occurred; there has been only a sucking-away of creative breathing space before the inexorable advance of a slogan which purports to foster change while it in fact reinforces the status quo.

But it isn't just creative breathing space that's been sucked away. The fear of 'appropriation of voice' has sucked away any apparatus by which we might come to understand a person of another social circumstance, another country, another culture. Take the attitude to its extreme, and it undermines the very assumptions of speech: that, through language, the experience of one human being may be conveyed to another.

At the end of his essay, de Zengotita writes:

What radicals should be doing right now is studying and thinking. You need to put in your ten years at the library, the way Marx did. You need to be figuring out what makes human beings tick and what, if any, direction is to be found in history. And I don't mean some half-assed sci-fi anarcho-Gaia nonsense you cobbled together before you dropped out of Bard; I mean serious study, working toward an alternative to a global bourgeois democracy. What radicals need most right now isn't action but theory.

I might revise that - not just theory, but fiction. 'Put down your Foucault,' says de Zengotita. 'Take up your Voltaire.' And, I would add, your Proust. And your Tagore. Your Ovid, your Achebe, your al-Mutanabbi, your Faulkner, your Borges, your Blake.

I'm still not running off to be a human shield in the Middle East. And I still feel a bit like I exist in an intertidal zone between my public values and my private life. But I have come to see that this intertidal zone is not the no-man's-land I thought it was. It is inhabited; not only that, it has language. You and I may talk with one another. It could be that this 'no-man's-land' is itself the sort of 'common ground' de Zengotita seeks.

De Zengotita, Thomas. 'Common Ground: Finding Our Way Back to the Enlightenment'. Harper's Magazine 306.1832 (January 2003). 35-44.Heaney, Seamus. 'Away from it All.' Station Island. London: Faber & Faber, 1984. 16-17.

Heighton, Steven. 'Horse & Train'. The Admen Move on Lhasa: Writing and Culture in a Virtual World. Concord, Ontario: Anansi, 1997. 29-33.

Henighan, Stephen. 'The Terrible Truth About "Appropriation of Voice"'. When Words Deny the World: The Reshaping of Canadian Writing. Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine's Quill, 2002. 63-69.

Whetter, Darryl. 'Kwump, Kwump, Kwump'. The New Quarterly 84 (Fall 2002). 142-151.

Whitman, Walt. 'Year that Trembled and Reel'd beneath Me'. Walt Whitman: The Complete Poems. London: Penguin, 1986. 333.